Managing Parasite Resistance

Many cattle producers now face the growing threat of parasite resistance. That doesn’t mean you should forego attempts to control parasites in your herd, but it does mean you’ll have to work smarter to defeat the bugs that can become profit robbers.

“We need to work more in harmony with nature,” says veterinarian Ray Kaplan, department of infectious diseases at the University of Georgia’s College of Veterinary Medicine. “We have to get rid of our drug addiction mentality. The drugs will remain an important component of parasite control, but they can’t be viewed as the only solution.”

Manufacturers of parasite control products are now urging cattle producers to implement parasite control strategies that will help slow the spread of resistance. Veterinarians remind producers that viable parasite control programs are needed to minimize economic losses and health problems. Those include: decreased calf weaning weights, sub-standard fertility and reproduction, reduced milk production, compromised immunity, and clinical disease from parasitism.

While economic losses are real, producers are urged to adopt more critical thinking about parasite control.

“We have to deworm less and deworm smarter,” Kaplan says. The first step toward that goal is to recognize that “every single cow on pasture is infected with these intestinal and stomach worms, but infection is not the same thing as disease.”

Kaplan says grazing animals have evolved in the presence of parasites, and they have the mechanisms to cope with them. The problem is when cows become over-burdened with worms. The rise of drug-resistant parasites means producers must become more educated about treating their animals.

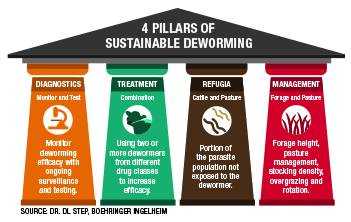

Effective parasite control now involves more than just alternating products. In fact, parasite researchers recommend using two classes of dewormers (typically benzimidazole and macrocyclic lactone) for both effectiveness and to help curb dewormer resistance issues.

Because it is natural for cattle to have parasites, it is not natural to try and raise cattle free of parasites, Kaplan says. “In fact, it is impossible to achieve. Attempting to eradicate worms only leads to more drug resistance.”

Better grazing management along with targeted parasite control is key to fighting parasite resistance. Kaplan says research has shown 75% of the worms in a pasture are in the bottom 2" of the grass, and 90% of the worms are in the bottom 4". In other words, the harder you graze your pastures the more worms your cattle will ingest.

“So, if you’re optimally managing your pastures, you’re also optimally managing parasites, and this is a really important natural thing that we can do,” Kaplan says.

Serious parasite problems often indicate overgrazing, and won’t be as easily solved with drugs as in the past. In fact, trying to solve such problems with dewormers will only result in more drug resistance.

A better solution, Kaplan says, is to seek the right balance of grazing management and parasite control. A key component of this strategy is what he calls refugia, the proportion of the worm population not experiencing the drug. Refugia are in untreated animals and eggs/larvae on pasture.

Refugia helps keep the resistant genes diluted in the parasite population, resulting in reduced or slower development of resistance across the parasite population.

“If we can maintain refugia we can help maintain a majority of drug-sensitive worms,” Kaplan says. “Failure to manage refugia is considered the single most important factor in the development of resistance.”

In practice, maintaining refugia is simply not trying to kill all the worms on your ranch. Kaplan says to consider only deworming cattle that are not performing well or are otherwise displaying signs of a heavy parasite load. He suggests treating only 80% to 90% of your herd, leaving the best-looking untreated. He calls this selective non-treatment.

Dewormed cattle will only have drug-resistant worms remaining, which means all the eggs shed in the pasture from those animals will populate the next generation of larvae which will produce drug-resistant worms. Over time, the resistant worms become dominant and the drug stops working.

“However, if we leave 10% to 20% of the herd untreated, the next generation of worms will still remain susceptible because we’ve diluted the resistant worms with the susceptible worms from the untreated animals,” Kaplan says. “That’s how refugia works in terms of the overall population.”

Given the spread of resistance, veterinarians now recommend using drug combinations.

“Combinations slow resistance because more resistant worms are killed, and the presence of refugia is essential to realize the full benefit from combinations,” Kaplan says.

The evidence tells veterinarians combinations of anthelmintics help slow the development of resistance and controlling worms once they become resistant.

To determine the presence of resistant parasites, the most effective method is the Fecal Egg Count Reduction Test (FECRT). Collect a fecal sample prior to treating animal with an anthelmintic, and another sample approximately two weeks later. If the parasitic egg count in the post-treatment sample is reduced by less than 90% compared to pretreatment, evidence of resistance exists.

Most veterinarians can perform the fecal egg counts. A general recommendation is to test at least 20

randomly selected animals, or the entire group if it’s fewer than 20 animals.