Researchers Assemble Genomic "Jigsaw" of Cow Gut Microbes

Using high-tech tools, Agricultural Research Service (ARS) scientists and their cooperators have taken a deep dive into the microbial "soup" of the cow's rumen, the first of four stomach chambers where tough plant fibers are turned into nutrients and energy.

Ultimately, such efforts could lead to new ways of ensuring the health and wellbeing of cows as well as improving their production of milk, meat and other products, noted Derek Bickhart, a research microbiologist with ARS' U.S. Dairy Forage Research Center in Madison, Wisconsin.

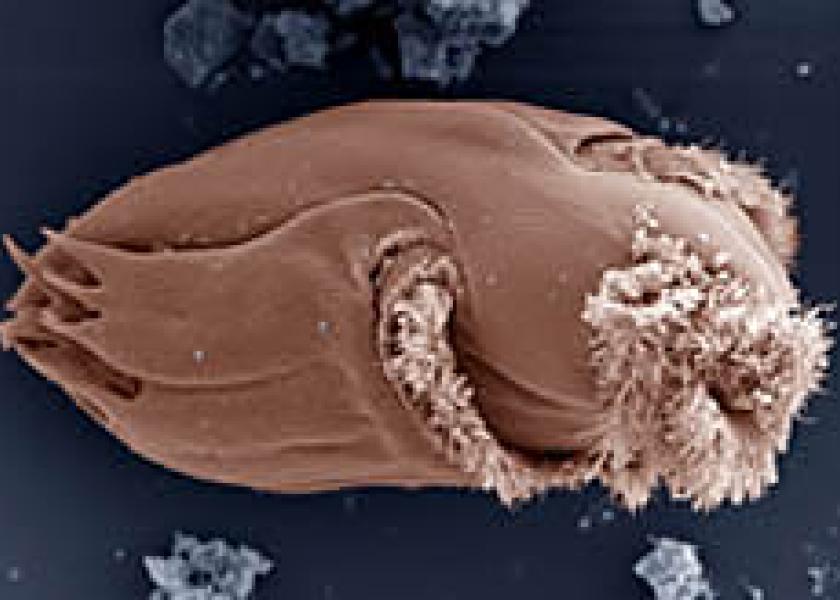

Annually, Americans drink about 18 gallons of milk (e.g., whole, skim, low-fat) per capita and eat about 59 pounds of beef. The cow's ability to meet this demand begins with a symbiotic community of microbes that inhabits its rumen—bacteria, protozoa and fungi among them.

"Compositionally, the rumen is unique because it contains organisms from all three kingdoms of life: Bacteria, Archaea and Eukaryotes. All of these organisms work in tandem to consume plant matter, and the byproducts of their digestion are used by the cows to produce meat and milk," explained Bickhart, who is at the ARS center's Cell Wall Biology and Utilization Research Unit.

Bickhart estimated there are over 30,000 species of these rumen dwellers, yet fewer than a couple thousand have been adequately characterized. That's left a gap in researchers' understanding of what role each species plays as part of a larger community known as the "microbiome." Researchers also want to learn what a microbe's absence or even proliferation can mean to the cow's wellbeing and performance—from withstanding costly diseases like mastitis, to producing important milk fats.

Now, Bickhart and colleagues are getting a better handle on the situation. Using the latest advances in sequencing equipment, they've devised a way to read the chemical coding of DNA fragments from the microbes and assemble the pieces into whole genomes using special algorithms. From this, they created an ordered genomic map of the entire rumen microbiome that will make it easier to identify individual members and their functions.

In the past, these sequence reads were limited to chemical units of measure known as nucleotide base pairs that fell in the 100 to 500 base pair range. With the new method, the researchers obtained reads of 9,000 to 30,000-plus base pairs—an increase resulting from the team's use of a long-read commercial sequencer (PacBio Sequel) and the new Proximeta Hi-C method. Full details appear in the August 2019 issue of Genome Biology.

Among other benefits, longer DNA reads make it easier to identify genes that can reveal what a particular microbe does or how it differs from other closely related species.

"While we haven't completely mapped the genomes of all rumen microorganisms in our study, we've come closer than those in the past and also identified new biological facts about the community that we didn't know before," said Bickhart.

His collaborators and co-authors on the Genome Biology paper include scientists from three other ARS locations, five universities in the U.S. and abroad, two biotech firms, and the National Human Genome Research Institute in Bethesda, Maryland.

The team's use of its specialized DNA extraction and sequencing procedures also revealed new insights about another denizen of the cow rumen, namely "bacteriophages"—viruses that highjack the genomes of bacteria to replicate themselves. In all, the team identified 188 bacteria-phage interactions, including host preferences, lifecycle and impacts on the microbe's metabolic activity.

"On the direct application side, knowledge of the rumen microbial community will be critical to estimating the feed efficiency of cattle and identifying microbes that contribute directly to milk fat production," said Bickhart.

For more on the influence of microbial communities on cattle nutrition and health, see these articles from BovineVetOnline: