A Healthy Calf starts with Fetal Viability and Well-Being

Key to most beef and dairy producers’ profitability is a healthy, high-quality calf crop. So, when an embryonic or fetal calf death occurs, it’s discouraging at best for your clients and a significant financial loss at worst.

“The losses can be associated with not only fetal death, but a prolonged open period, especially with early embryonic death, delayed peak lactation if we’re talking about dairy cattle, and of course, increased culling rate,” says Andrea S. Lear DVM, MS, PhD, DACVIM (Large Animal), assistant professor, Large Animal Clinical Sciences, University of Tennessee.

The potential impact of those factors drives home the value of veterinarians being able to assess fetal viability and well-being to increase the possibility of having a productive, healthy baby born at the end of gestation.

Two Important Factors

Lear defines fetal viability and well-being as a combination of two things. “It’s taking into account how the baby is doing at any point in gestation,” she says. “Second, it’s determining what the likelihood is that the baby is going to survive outside the uterus, once it’s on the ground.” 1

A 2020 meta-analysis published in Animal Reproduction Science indicates the levels of mortality found today on dairy and beef farms. It says overall late embryonic and fetal mortality (LEF) in U.S. beef cattle is 5.8%, report researchers at Texas A&M University. 2

That is significantly less than what occurs in dairy cattle. “In most reports, there is an estimation of late embryonic mortality of lactating dairy cows of between 10% and 20%, although in some studies results indicate there is about a 7% late embryonic loss in dairy,” the researchers wrote.

Cameron Knight, veterinary pathologist at the University of Calgary, believes the standard of acceptable, herd-wide fetal calf loss on North American dairy operations is much lower, about 1%. Producers should be concerned if that percentage climbs to 4%, he says.3

Who’s At Risk? As a rule of thumb, Lear says the animals you want to evaluate or monitor for fetal viability and well-being are any pregnant animal that has experienced any sort of stress. “That could be stress associated with transport movement or disease, if that animal is suffering from a system illness or some viral infection,” she says.

In addition, she says consider any animals at risk of abnormal offspring syndrome, including somatic cell nuclear transfers (clones) or in vitro produced embryos.

“These animals are genetically more valuable in theory,” she says. “More money and time were spent to create these embryos and implant them into an appropriate recipient, but they're also more likely to suffer from challenges, especially in late gestation and in the neonatal phase. So, these are the patients that are the maternal and fetal patients that we would probably be assessing.”

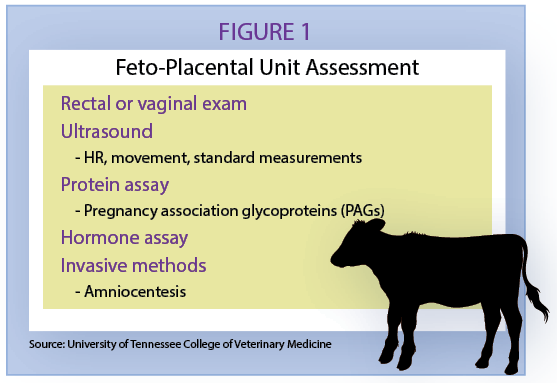

There are numerous practices veterinarians use to assess the well-being of the feto-placental unit (Figure 1). They vary significantly in how useful they are in practice, Lear say.

A Poor Indicator

Measuring circulating maternal hormones is a relatively poor indicator of how the fetus is doing but can give you an idea of whether the placenta is doing its job, according to Lear.

“The first thing we can monitor is progesterone, being that's the pregnancy hormone or the hormone required for maintenance of pregnancy,” she says. “You know, we expect at least in cattle for the placenta to eventually take over the massive production of progesterone after middle to late gestation. However, the hormone assay doesn’t typically tell you whether there is some fetal compromise present.”

Simple Yet Effective

Rectal and vaginal examination is a simple method to quickly assess the developing fetus, Lear says.

Via rectal examination, fetal movement is easily detectable in later gestation. Upon vaginal exam, the external os of the cervix should be closed until the last weeks of gestation. Any dilation could indicate impending fetal expulsion.

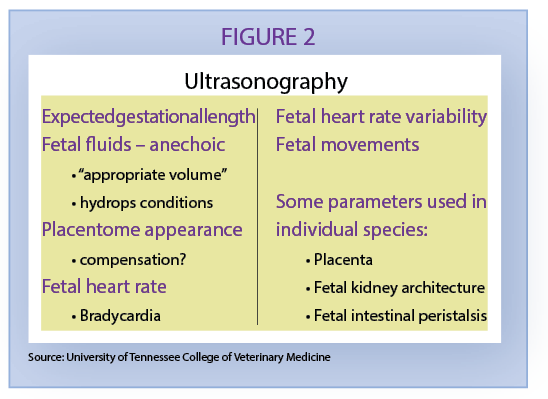

“Fetal ultrasounds or trans rectal or trans abdominal ultrasonography is something that you can apply today in the field,” she notes. (Figure 2)

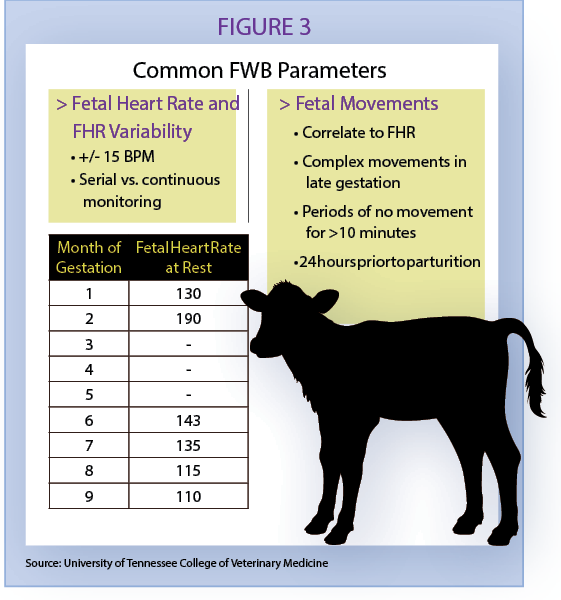

An objective measurement of fetal well-being includes fetal heart rate. Expected fetal heart is determined gestational age.

“Continuous or multiple measurements, allowing creation of a mean heart rate is best as fetal heart rate variability is expected during phases of movement and sleep by the conceptus,” Lear says. “This should also be taken into account when assessing fetal movements. Overall, bradycardia is most correlated with poor fetal wellbeing and fetal loss.” (Figure 3)

Lear says to do the measurements when the cow’s locked up and relatively calm, because the fetal heart rate will be altered based on maternal heart rates.

“There is not a lot of literature providing insights on gestation between three to five months,” she notes. “But we do have a fair bit of information on the first couple months of gestation, and then a fair bit between six and nine months of gestation in cattle.”

As parturition gets closer, you can expect to see a decrease in fetal heart rate. Be concerned if that rate is too low or too high. “At 130 to 140 death has been associated with neonatal death at parturition,” she says.

You can expect to see some complex movements at the end of gestation. And occasionally, you will see periods of rest.

“But we shouldn't see periods of no movement for over 10 minutes, unless they’re right at the end of gestation, when those animals are really quite developed and just waiting to come out,” she says.

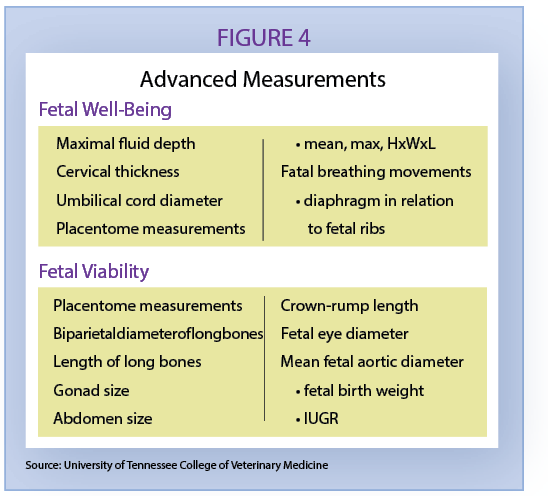

Along with fetal heart rates, there are advanced measurements you can use to assess fetal well-being and viability (Figure 4).

PAGs Offer Promise

Pregnancy Association Glycoproteins (PAGs) are produced by the binucleate cells of the ruminant placenta and can be used to diagnose pregnancy.

A 2019 study published in Theriogenology says, “Increased circulating concentrations of PAG early in gestation have been correlated with pregnancy success and decreased concentrations are predictive of impending embryonic mortality in both beef and dairy cattle.”4

Lear says research shows that PAGs are much more elevated in clone calves and in cows carrying clone calves compared to normal, non-cloned calves.

“And that kind of makes sense, right? We've all dealt with clone calves in the past where we can kind of see this adventitious placenta, where these placentomes get really big and really wonky and, even the baby itself can be quite large,” she says. “It kind of makes sense if the placenta is so much bigger and maybe a little more adventitious that their PAG concentration would correlate or be associated with those masses.”

Lear says she expects more research to be done with PAGS and that they will offer an increasingly viable assessment of fetal well-being in the future.

References

1Lear, Andrea. Determination of Fetal Viability. American Association of Bovine Practitioners Proceedings of the Annual Conference. 2020.

2S.T. Reese, G.A. Franco, R.K. Poole, R. Hood, L. Fernadez Montero, R.V. Oliveira Filho, R.F. Cooke, K.G. Pohler. Pregnancy loss in beef cattle: A meta-analysis. Animal Reproduction Science. 2020. Volume 212; 106251.

3Knight, Cameron. 6 Steps to help Assess Fetal Calf Loss. Bovine Veterinarian. Published online. 2021, Nov. 22.

4S.T. Reese, T.W. Geary, G.A. Franco, J.G.N. Moraes, T.E. Spencer, K.G. Pohler. Pregnancy associated glycoproteins (PAGs) and pregnancy loss in high vs. sub fertility heifers. Theriogenology 2019.05.26. Epub 2019, May 31.